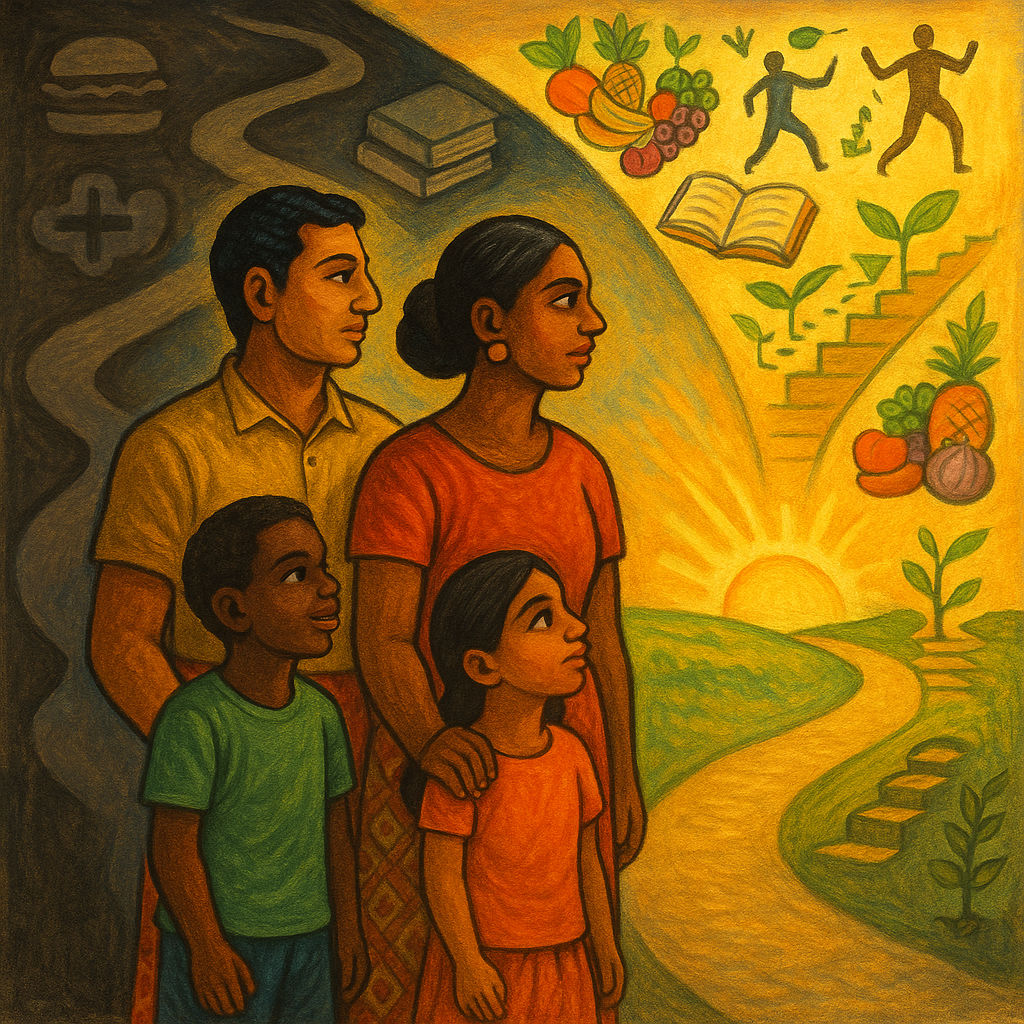

The Vicious Cycle: Unlocking Family Growth Through Food, Education, and Health – A Global Perspective

It's become crystal clear to me that the growth of a family, especially when it comes to their kids going to the next level, breaking free from inherited constraints, depends so much on how they behave with their spending on three absolutely core areas: food, education, and health. I'm convinced that the basic behaviour, their level of education, their ingrained thinking patterns, their actual expenditure patterns, and their overall lifestyle – and critically, their inherent potential to grow and, even more importantly, their children's potential to grow – are all powerfully reflected in how they think, behave, and specifically, how they choose to spend on these three fundamental aspects of life. This isn't just theory; we see it playing out in communities from rural Sri Lanka to urban centers in the West, in every development indicator that tracks household well-being. Studies, for example, often link higher maternal education directly to better child nutrition and health outcomes, showing how these choices ripple through generations.

Now, why do people, despite all the awareness campaigns and well-meaning advice, often ignore what seems like straightforward wisdom on health and education? It’s not usually because they're ignorant, or even that they don't want a better life. I think it's because their minds are often fixed, almost programmed, by their family's long-standing behaviour and influence. It's a powerful current, isn't it? They go by their perception, what they've always seen and known, what their elders did, what their neighbours do. This isn't just about income; studies on behavioral economics in diverse populations show how cognitive biases and social norms powerfully shape choices, often overriding rational self-interest. For example, even when healthier food options are available, ingrained habits or community preferences can steer families towards less nutritious, more familiar choices.

Take education, for instance. For many, globally, it’s perceived as a very fixed cycle: "go to tuition, get a certificate, find a job." That's the end goal, the accepted path to progression. They might not be looking beyond that narrow corridor, not exploring what else education can offer – critical thinking, creativity, adaptability, entrepreneurial skills – or how it truly opens doors to non-traditional, more lucrative avenues. In many developing contexts, the pressure to gain immediate employment often overshadows the long-term benefits of sustained, quality learning, perpetuating a cycle of limited opportunities.

With food, it’s often a similar story. There’s frequently no real attention to detail on how healthy the food really is, beyond its immediate ability to fill a stomach or provide energy for work. It’s about what’s cheap, what’s readily available, what tastes good, what's culturally familiar. The profound, long-term health implications – how diet affects energy levels, how it shapes a child's cognitive development and their concentration in school, how it impacts susceptibility to chronic diseases later in life – these often get ignored, or simply aren't factored into daily decisions. This is evident worldwide, where nutritional deficiencies or obesity can coexist in the same communities, driven by complex webs of perception, affordability, and tradition.

And health itself? It's often approached with what I call a "frog in the well" kind of thinking. People know what they know, they do what they do within their immediate familiar sphere, and they might not seek out or truly value new information on preventative health, or holistic well-being, until a significant problem, a serious illness, is already at their doorstep. The idea of proactive health investment, of small daily habits that build long-term resilience, often takes a backseat to reactive crisis management. This "curative over preventative" mindset isn't unique to any one region; it's a deeply ingrained human tendency, often reinforced by traditional beliefs and limited access to comprehensive health education or services.

This profound lack of proper exploration, of looking beyond their immediate surroundings or ingrained habits, means families aren't able to find, consume, and really digest new and latest information on progression. They miss crucial insights that could transform their lives. And what does this create? A vicious cycle, that's what. The way they behave, what they prioritize their limited resources on, limits their understanding and, crucially, their children's understanding, which then tragically reinforces those same behaviours in the next generation. It’s a self-perpetuating loop, a multi-generational trap that is incredibly tough to break, seen in patterns of intergenerational poverty globally, where children born into disadvantage often face similar disadvantages as adults.

So, the big question, the one I'm really grappling with in thinking about this venture, is: what can a family, anywhere in the world, do to break this vicious cycle to truly open the door for growth? It feels like we need a strategic toolkit, a set of actionable principles that can actually help them nudge themselves towards better outcomes.

We've talked about things like getting into marginal improvements – those seemingly small, consistent changes in daily habits, whether it's adding one extra vegetable to a meal, reading to a child for fifteen minutes longer, or walking an extra ten minutes each day. These aren't huge leaps, but their power lies in their consistency, their quiet accumulation. Then there's the monumental power of compounding growth, where these little investments today, whether in health habits, learning curiosity, or financial literacy, pay off massively, almost exponentially, over time. Think of how a child’s early exposure to diverse books can compound into a lifelong love of learning and critical thinking.

Applying the 80/20 rule (the Pareto Principle) could be a game-changer too: identifying the 20% of efforts in food, education, or health that will yield 80% of the results, and intensely focusing there. For instance, what are the few key nutritional changes that provide the biggest health benefits for the least effort? Which educational activities provide the most cognitive stimulation for a child? And definitely, getting rid of the paradox of choice – simplifying decisions, providing clear, actionable pathways, and focusing on what truly matters, rather than overwhelming people with too many options which often leads to inaction. Behavioral economics has shown that people often choose nothing when faced with too many choices.

But what else? What else can help fix it, empower families globally to break free? We need to consider how to introduce "nudges" that gently guide choices without restricting freedom. This could be as simple as making the healthier food option the default, or structuring educational information in easily digestible, actionable chunks. We also need to think about fostering "growth mindsets" within families, moving away from fixed perceptions of their capabilities or their children's potential, towards a belief that abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work. This can be supported by celebrating effort and progress, not just inherent talent.

Furthermore, building community support networks can be crucial. When families see their peers making positive changes, it creates a powerful social norm that reinforces new behaviors. This is where localized, culturally sensitive programs that involve the whole community, not just individual families, can have profound impacts. Think of community kitchens promoting healthier cooking practices, or local reading clubs for children and parents.

Ultimately, this isn't about grand, sweeping changes overnight, dictated from above. It's about empowering families, regardless of their background or current circumstances, to see those little levers, to make those seemingly small shifts in their daily lives that can, over time, completely change their trajectory and open up a whole new world of potential and opportunity for themselves and for their children. It's about equipping them, wherever they are in the world, to look beyond their well, to actively seek out and internalize the knowledge and the practices that truly help them grow, thrive, and define their own better future.

Comments